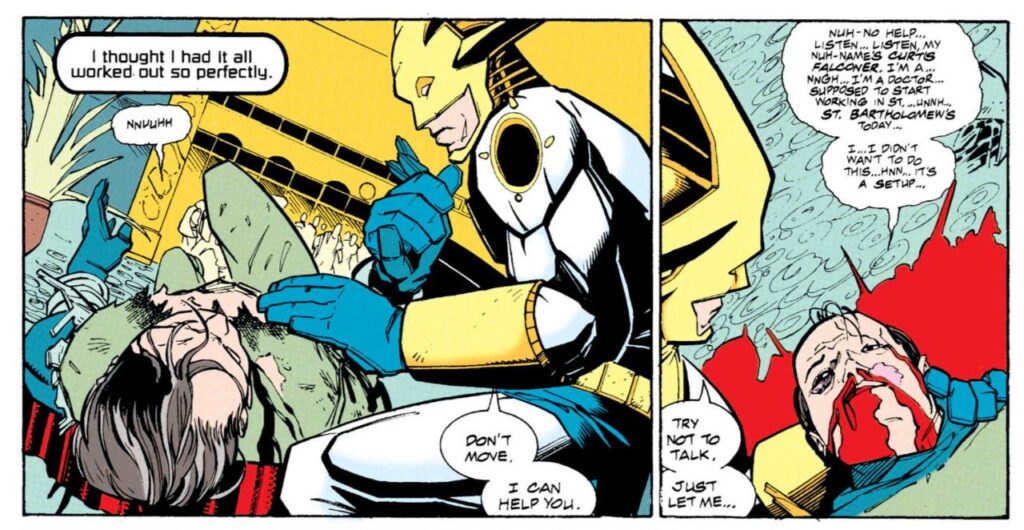

Aztek is a deconstructed superhero. He does all the things a modern, ’90s superhero does—has a mysterious past, keeps a secret identity, fights supervillains, saves people from society’s ills, joins the Justice League—but he does it intentionally. The reason behind his actions just may not be what he thinks it is.

Aztek is different from other superheroes of the era because he’s not just the cool, stoic, gritty face of the ’90s. What makes Aztek unique is what he chooses to do when confronting modern problems.

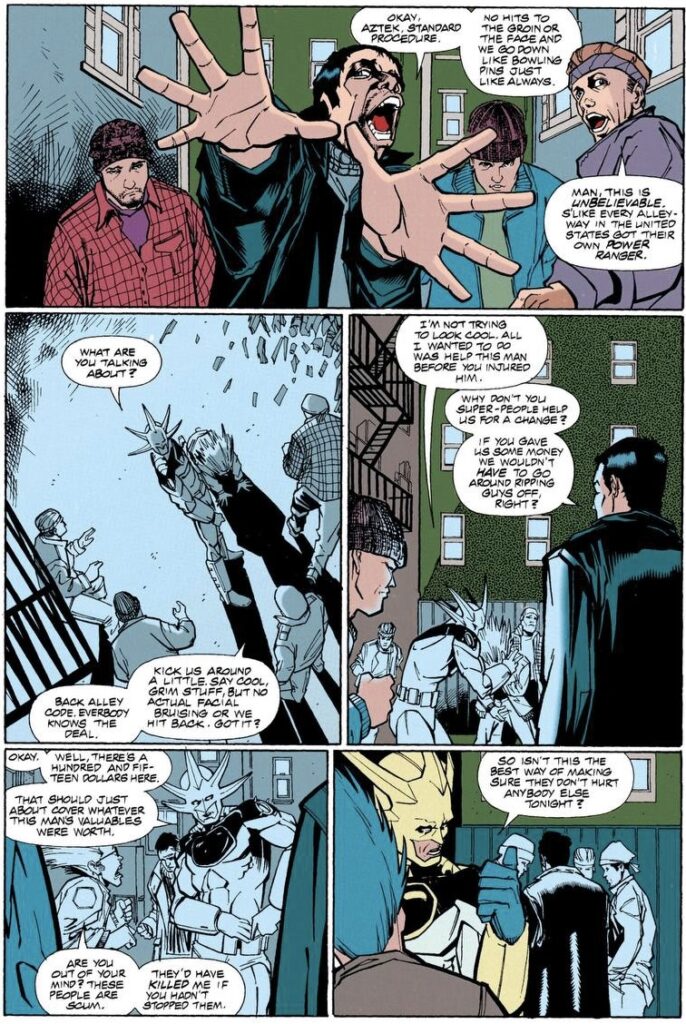

While stopping a mugging, Aztek eschews violence and gives the muggers his own wallet to stop any further violence. His gentle approach and mercy save his life later in the issue.

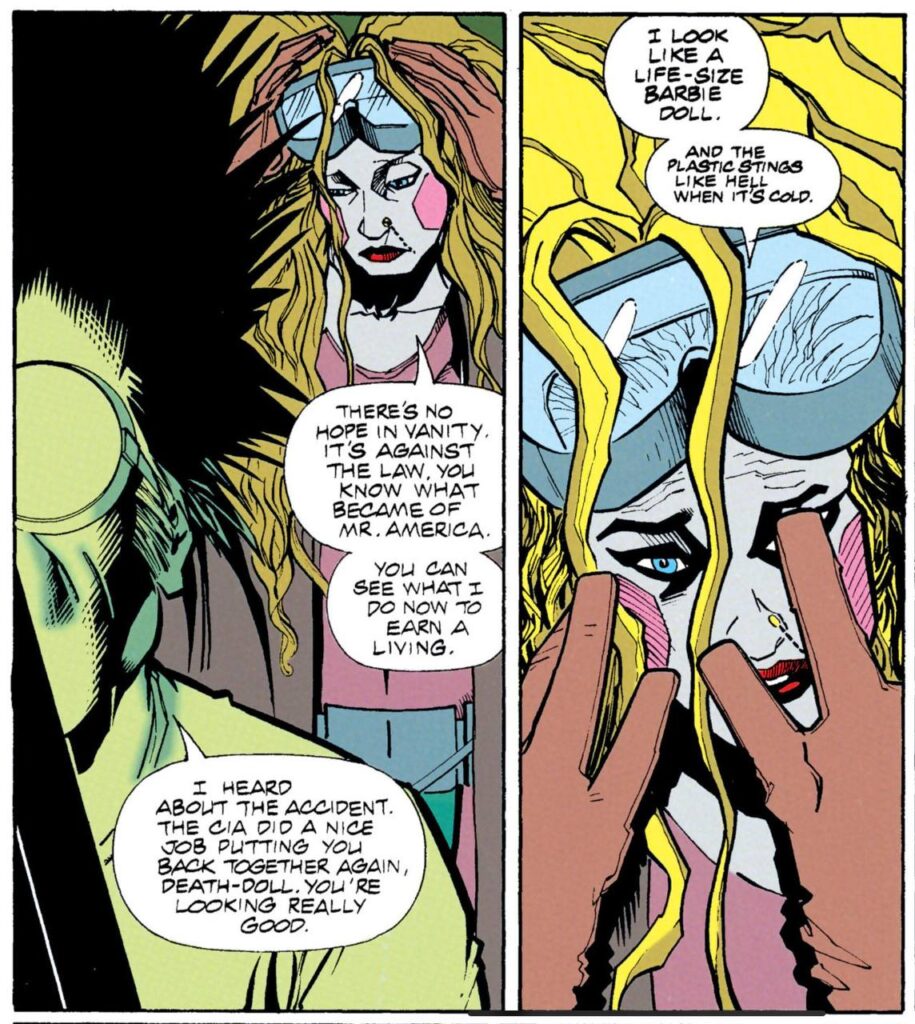

The interesting thing about Aztek’s villains is that they’d have been protagonists in other books. Aztek’s “villains,” more often than not, see themselves as heroes, and tend to be self-destructive, tormented souls at the mercy of unfeeling monolithic corporate or government interests—a intentional stark comparison and contrast with the heroes of the time. 1996 was not a kind time to be a new superhero; as likely as not, they’d be written as merciless government operatives or crazed vigilantes.

Aztek explores and examines superhero tropes and lets its protagonist decide whether to follow them. Any number of other paint-by-number superhero books of the late ’90s were machismo, posing, and costumes with no sense of morality or self-reflection. Aztek shows all its characters just a little mercy.

Even the name of Aztek’s chosen home city, Vanity, might be a veiled reference to Image Comics, the artist-owned, (at the time) style-over-substance superhero factory that was threatening to outpace DC and Marvel’s classic superhero morality tales. There’s no hope in Vanity, except where Aztek creates it.

Under different writers, the story of Aztek would be much less intriguing—it’s practically a beat-by-beat instruction manual on how to introduce a new superhero to DC Comics in the late ‘90s. Again, though, it’s a deconstruction of the superhero story, so someone else in the story who knows superhero tropes is manipulating Aztek for their own ends. Had the series been allowed to continue, it would have been a very satisfying payoff.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the art by N. Steven Harris, Keith Champagne, and Mike Danza. Aztek is a scratchy, gritty, textured book, with flat, muted colors, instead of the popular oversaturated computer colors popular at the time. Aztek’s white and gold costume gleams in comparison to his surroundings in the supposedly-cursed city of Vanity. It’s stylish without being distracting.

Of course, this being the ‘90s, Aztek was canceled ten issues into his run. His story continues in JLA.

Aztek, the Ultimate Man is a Good Thing.

JLA Presents: Aztek, the Ultimate Man was written by Grant Morrison and Mark Millar, penciled by N. Steven Harris, inked by Keith Champagne, colored by Mike Danza, and lettered by Chris Eliopoulos and Clem Robins, and published by DC Comics.

Aztek is such a weird beast of a book. Instantly identifiable as a 90’s!(tm) book, but at the same time feels like a low key throwback to the late Silver Age/early Bronze Age.

I see it as a commentary on ‘90s!(tm) books. Most of his villains are heroes, at least in their own heads—-so really, he’s tackling the comic industry circa 1996.

I was around in the 90s and don’t remember Aztek. I’m definitely interested in reading more.

Would you like a copy?

Yes please!

Sent!

As someone with indiginous origins this intrigues me – how many books were published?

Ten issues of the original comic back in 1996 and 1997, and it was collected just a few years ago in a single reprint paperback volume. Just because it was canceled early, it doesn’t go terribly deep into Aztek’s personal history, but he is a member of the Brotherhood of Quetzalcoatl and of indigenous origin himself. The book was written by two Scotsman nearly thirty years ago, so a grain of salt may be needed. If you have a Kindle-compatible device, I’d be happy to send you a copy!

That would be awesome, thank you!

Sent!